"Year" is not a unit of measurement for experience

How to deprecate yourself and win your growth

Resumes, job ads, personal intros and even funerals have one thing in common: they usually use “year” as a unit of experience in something.

This is fundamentally wrong! The quality of experience cannot be measured with a quantitative metric.

Measuring experience by years is like estimating the strength of a rope by its length!

Year in nature

Let us start with what we know: a year is the time it takes for the earth to go around the sun one revolution. Some animals sleep half of that time while others go through multiple generations. A hard year may wipe out a species while making another one stronger.

The point is: not all years are the same and not all years are experienced the same.

Take trees for example. Seeds become saplings (young trees) in a year. Trees get thicker with each year.

Growth is more significant at the start. After that, time adds strength but not necessarily in a significant way. With enough time, the tree decays and falls under its own weight.

There is a point of diminishing return where more time doesn’t mean more strength.

We humans tend to think of ourselves as separate from nature, yet our growth path is not that different from a plant!

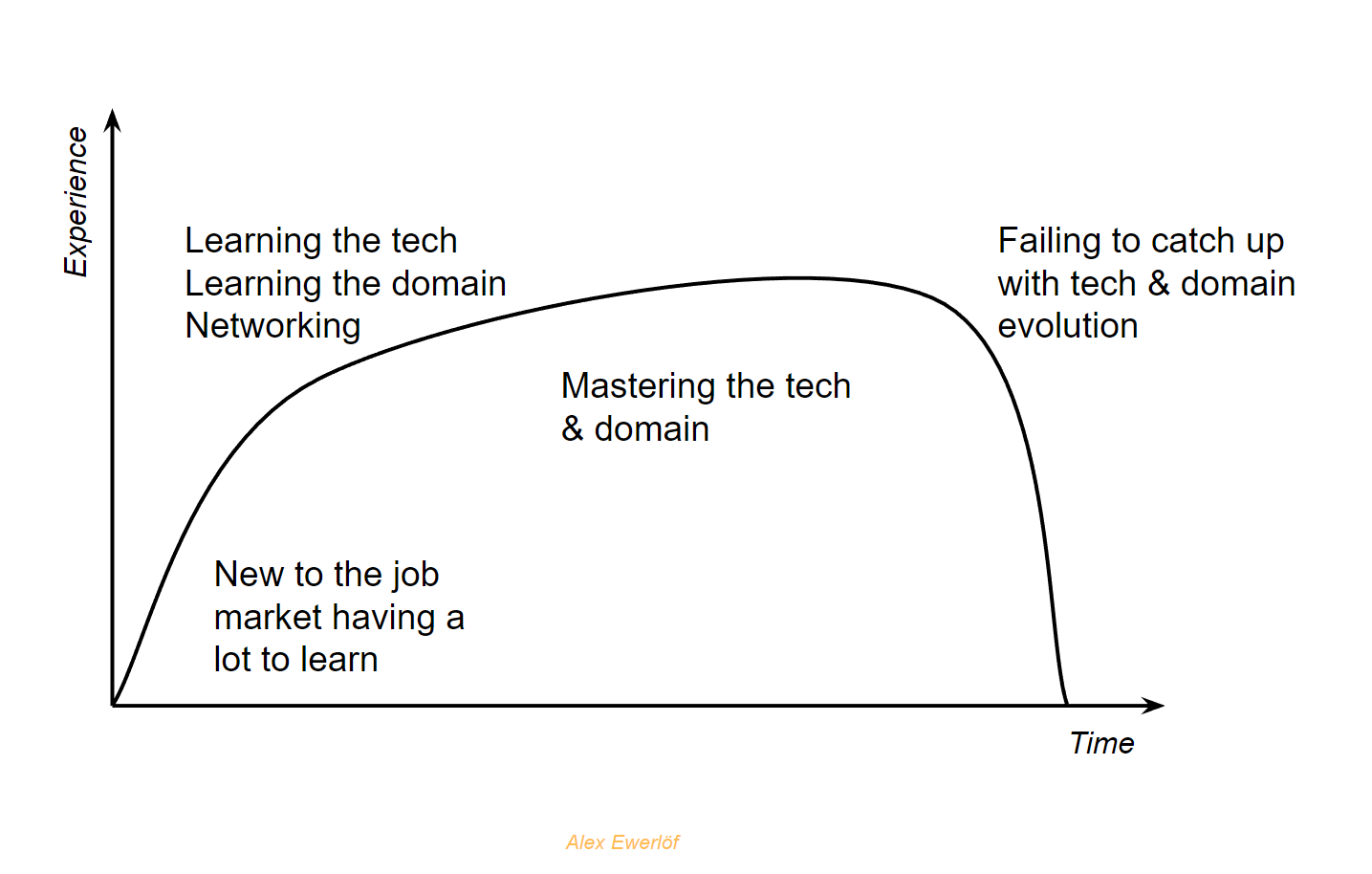

This is how the career growth of knowledge worker looks like:

Not everyone gets to see the end but it’s inevitable. If not for the ever-evolving tech and domain landscape, the brain (our core tool) diminishes over time. At some point we fail to unlearn the old and learn the new. At some point, it is cheaper to hire a fresh graduate with up-to-date education, unlimited energy, and ambition but less pay demands and baggage (past experience and opinions).

The inability to let go of old knowledge and adopt new knowledge blocks the growth of many senior engineers. 🧀🐭 For knowledge workers, the ability to unlearn is as important as the ability to learn.

Where are our elderly?

In what resembles the fermi paradox of a knowledge worker career, it’s fair to ask:

where is are our elderly?

Does the demography present at our workplace really represent the demography of knowledge worker graduates 40 years ago?

I know of some former programmers who ended up as taxi drivers, antique dealers, or stock investors.

The lucky ones climb the corporate ladder high enough not to be threatened by fresh talent but avoided by the very people they are supposed to “empower”.

They function as the wise elderly that our species has evolved to look up to in times of uncertainty. They have mastered the art of delivering advice that is vague enough to apply to the common pain but not specific enough to justify the pay.

Those are the lucky ones. There is also a champion minority. I know of a handful of them who defy the laws of nature and still code at the age of 60+.

I have immense respect for any knowledge worker who is still in the game in an industry that is known for all sorts of bias including ageism.

If you are aiming to be among the champions, think again! Are you in the top 1% of your industry right now? If not, it doesn’t hurt to have a backup plan.

Stimulus and response

Back to where we started. Year is the wrong metric to measure experience.

The quality of experience depends on two main factors:

Stimulus: the challenges one is exposed to

Response: how one handles those challenges

Being exposed to the same type of stimulus reinforces the response. Variations in the stimulus leads to mastery. Practice makes perfect.

There’s a point of diminishing return where longer exposure yields minimal improvement.

That’s the best time to change and jump on faster growth tragectory:

If we internalize the fact that there’s an end, why passively wait in fear instead of actively taking control and embracing change?

We are notoriously bad at understanding exponential change.

Nature is efficient. It is natural to want maximum pay for minimal effort. Why quit at the peak?

We all crave comfort, but life has other plans.

Artificial death

You’ve probably heard:

What doesn’t kill you make you stronger

It’s a testimony to the impact of challenges on our very essence. We are an adaptable species and that is key to our survival and evolution.

The thesis is: exposing ourselves to challenges, even synthetic ones, makes us stronger. i.e. more experienced.