When companies feel stressed

How a cost-cutting strategy led to the greatest collaboration effort of all time

Considering the current economic turmoil that followed the pandemic and war, many companies are in the cost-saving mode. Sometimes, the “peace time” and “war time” terms are used:

Peace time: the focus is on effectiveness, doing the right thing

War time: the focus is on efficiency, doing the thing right.

In times of stress, companies go into war mode, i.e., the focus is on efficiency and productivity.

The only way for the company to make a profit is to have a margin between the money it makes from its customers and the expenses. And employee payroll is usually the main chunk of those expenses. When that balance is threatened, layoffs are in order.

In the software sector, these were the headlines just in the last few days:

Oracle gears up to lay off thousands

Microsoft sells its lay off as reorg

Facebook (being nasty as usual) hides the lay offs behind performance reviews

Tesla being Elon’s show, lays off due to his “super bad feelings”

Ford lays off 8K

Google? keep reading…

Google has been a respected leader in the software industry for a long time. This internal memo from their CEO reveals some interesting bits:

Even a giant (both in terms of number of employees and revenue) is going into cost saving mode. The sh*t is serious! 😬

Although they're slowing down recruitment due to "uncertain global economic outlook", when they do hire, the focus is on "engineering, technical and other critical roles". Phew! 😅

Disclaimer: this post is by no means an endorsement of Google or layoffs. The goal here is to elaborate how war time strategy brings focus to a company.

"Scarcity breeds clarity"

Apart from slowing down hiring, Google asks employees to "consolidate where investments overlap and streamline processes". This is a call to focus on "pausing development and re-deploying resources to higher priority areas".

In the memo, Sundar Pichai says “scarcity breeds clarity” which really resonates with the story I am about to share.

My story from the days of glory

Back in 2016 I joined a media company. Little did I know, I was part of a newly established product and tech organization which was created solely to compete with Google and Facebook.

The reason? Media traditionally relied on advertisement revenue but since Google and Facebook knew way more about their users, they could deliver targeted advertisements. This was a more effective way to reach consumers and yielded a higher bang for the buck for advertisers. Google and Facebook ate the media's lunch!

But this media company wasn’t going down without a fight. Equipped with advice from McKinsey and enjoying deep pockets at the time, it threw money at the problem and hired some of the smartest people I had the honor to work with.

It was there where I first met an actual xoogler (ex-Googler) in the flesh! There were many, including the CTO. And a few from Facebook, Spotify, and other media companies. It felt like we took a page from the “Art of War”:

The opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself.

—Sun Tzu

Fast forward 2 years later (2018) it became apparent that a media company focusing on the small Nordic countries (Norway and Sweden) is no match for American giants all while traditional media was losing popularity.

The company broke in two halves and the CEO took the “better” half with him. You see, this wasn’t your average media company. It had diversified its portfolio through buying many startups, most of which were in the so-called “classified marketplaces” (like eBay or Craigslist). Most of those brands went to a new company led by the original CEO. The media part (where I was working) remained and got a new CEO.

The new CEO

Disclaimer: this is my recollection of the events written 4 years later. And just to clarify, I wasn’t in “the room” where these decisions were made. My information is based on hearsay. My narrative is about my experience being part of this transition.

It took a few months for the new CEO to find the ropes. Then came a benign announcement about some reorg in her immediate leadership team.

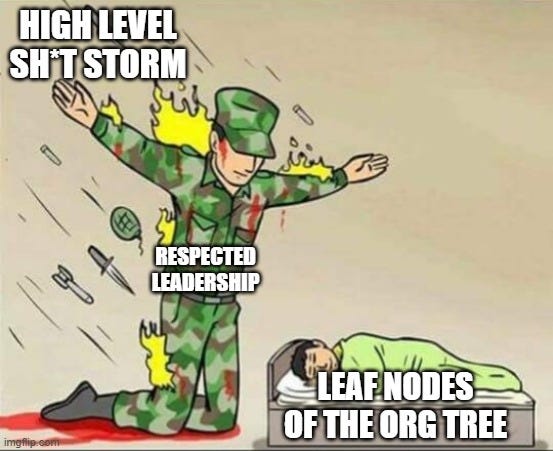

To us engineers at the leaf nodes of the organization tree, it wasn’t particularly big news. CEO could do whatever she pleases.

We couldn’t care less about those high-level changes. If anything, we were eagerly waiting for more to see a tangible change that justified breaking the company into pieces.

And more came! Over the next few months, the CEO reports started renovating their own sub-orgs and the changes eventually trickled down to our level.

Expect fast results

Throughout my time at that company, I remember “innovation” being a constant motto. In one form or another, it was everywhere, at every high-level communication, product planning and even the company slogan!

I didn’t see much innovation in the old days before the company split. We were just creating “yet another…”: yet another login screen, yet another CMS, yet another ad inventory, yet another news site.

I remember seeing an Oculus Rift VR headset at the office one day. I tried them for the first time. What an amazing experience!

I asked: “Why do we have these?”

I was told “to experiment with new ways of telling stories”.

Yet by the time I left 5 years later, I didn’t see any VR content on our news sites.

On retrospect, one of the main reasons that the company failed to capitalize its investment on the fresh top talent was time. It naively threw money at the problem and burned through its budget.

But it takes time for the new people to get to know the business, tech and organization. We had very smart people, but they didn’t get the time to deliver an impact. The market pressure was intense, and this last push was too late, no matter how expensive.

The failure of the new product and tech org and the ensuing collapse of the company was as much an external factor (traditional media losing popularity, market competition) as it was internal.

This was a classic example of “culture eats strategy for breakfast”. Becoming a smaller company and focusing on media was a step in the direction that matched the culture.

The culture that ate

In a truly Scandinavian spirit, each team enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. We were heavily siloed. Each team had their own tooling, process, plans and (depending on who you asked) different definitions of the company mission and vision.

Aligned autonomy is the holy grail of productivity. More on that in a future article.

I wouldn’t go as far as calling it “total chaos”. Somehow, through the good will, blood and sweat of engineers implementing e2e features across teams, it worked. Those handful of engineers cross pollinated between the silos and broke free from the thick walls of their silos.

It wasn’t a smooth ride though. The end users could see the consequences of the silos when they navigated the site.

We were shipping our organization structure to the end user.

The focus

It makes sense in retrospect: the new product and tech org was filled with smart people with high salaries. And when it came the time to lay people off like extra rows in an Excell sheet, it made sense to sort them by salary to maximize saving while minimizing head count loss.

At the top were the consultants. Nordic countries have very strong job safety laws that protect the workers. But for companies to stay competitive, they need a mechanism to cope with fluctuating needs in the market demand. And that’s where consultants come in. The laws are not as strict when hiring and firing consultants. For the most part, they are treated like regular employees, but they enjoy higher pay due to the higher risk that they take.

Layoff put their neck on the line first.

To do it in the most humane way, the consultants were offered a choice to either convert to full-time employees or leave. Many left, but a few took the offer.

As the company was inevitably slowing down its innovation, many ambitious skilled people jumped ship. There was a period where we got goodbye emails almost on a weekly basis. “It was an honor working with you, but now it’s time to take new challenges, blah blah”.

It’s a huge red flag when respected leadership leaves the company, and we had many. With every great leader we lost, a dam that was holding back shit broke. We were exposed! It was demoralizing.

It’s a lie to say I wasn’t speculating about leaving but the vacuum that was left by some of my smart ex-colleagues provided a great opportunity to learn and grow so I stayed and grew a lot just by filling in their seats.

One thing I really liked about the new CEO was her monthly live all-hands which ended with questions and answers. We used Sli.do to ask any questions anonymously, and the CEO answered honestly. Thanks to those monthly all-hands, we started to have a better alignment at a high level. It helped the entire company to get the same memo. It greatly facilitated our collaboration across teams because we were sailing towards the same north star.

I work with strategies these days. A proper strategy has a clear diagnosis paired with a guiding policy and coherent actions. At least that’s the format I operate upon based on the Good Strategy Bad Strategy. I didn’t see a single document with those elements, yet the entire company was aligned with the CEO.

The unwritten cost-saving strategy turned into a great opportunity for people across the board to bring their best and collaborate.

Smash them silos

I worked at the Core Platform team. Not to bore you with the details, we made a white label news site platform which could be used by any of the 20+ brands the company owned. We were at the epicenter of the action (or so it felt). But in every direction we looked, we saw silos.

We were sandwiched between the brands pursuing their own objectives and the upstream CMS teams which didn’t give what we needed in a timely manner due to being too distant from the end users. This was a symptom. The root cause was our tech fragmentation and lack of product-minded engineers.

Inevitably those silos followed their own objectives and priorities —sometimes conflicting. There was a lot of duplicated effort. For example, two brands had two different paywall implementations all the way to the edge CDN layer.

You cannot collaborate when you don’t coordinate —I used to say in frustration

The cost-saving initiative was an objective sent from heavens!

It helped smash those silos in the name of cost-saving. No more duplication of effort in the name of “innovation”. No more multiple solutions for the same problem. We had to join forces to work efficiently.

Gradually, the cost-saving strategy smashed those walls. It started with an initiative to consolidate our observability tooling which gave us great visibility into what’s running across the stack from the users’ browsers all the way to the CDN, rendering engine, API, config, and CMS.

We cross-referenced that data with our cloud bills to spot opportunities for cutting costs. Over the course of the next 12 months, we killed many servers, rewrote some to serverless and re-architectured part of the stack.

Generalist vs Specialist

The company terminated the expensive contractors and we, the regular employees, had to fill in. They also deprecated the specialized QA (quality assurance) or DevOps titles, which forced us, engineers, to put the operation hat on and fully own the quality aspects of the code.

There was an uproar internally, but as the time passed by, what didn’t kill us made us stronger. Personally, I learned a lot about operations and cloud computing during that period and took multiple courses on AWS and learned Terraform, Kubernetes, Datadog, etc.

I entered the company as a front-end specialist, dug into backend and quit as a fully grown SRE (site reliability engineer).

Up until that job, I had always written the code and thrown it over the metaphorical wall for the “DevOps” (operations in actuality) to handle. For quality control, I relied on the QA when it was available, and left it to unit tests when it wasn’t.

The new “generalist profile” that the situation grew us into, was indeed very empowering.

Not only could I touch anything from the CI/CD pipeline to the integration tests and performance monitoring, but I was also expected to. Hell, I had admin access to the most critical accounts behind the face of the company. My entire team did!

I’m sure the end users saw the benefit too because the sites became snappier as we did less behind the scenes and the things we did, we optimized for performance and maintainability.

FinOps

By the end of that year, my colleagues Emil and Martin and I practically acted as FinOps.

I remember that I provisioned an AWS Lambda for a hack day project and 2 weeks later, Emil was tapping my shoulder to shut it down. This would save us a grand total of 2.1 cents per month! We were savages like that!

What’s more, we started collaborating with other teams to find what tech stack they are running and whether there are different solutions to the same problem.

Previously our collaboration stopped at the API level. Now, we were taking a peek behind the curtain.

Sure enough we found a bunch of opportunities, which were mostly remnants of the good old autonomous days of that McKinsey-inspired product and tech org. We killed them when we could and rewrote them when we couldn’t. It’s not like we had anything better to do.

Our primary objective was to keep the lights on and the heads above water. This was existential. We were determined to cut the costs or a lay off would be inevitable.

Sidenote: a Swedish lay off is not as dramatic as it sounds. There are tons of safety nets in place to make sure you don’t end up sleeping in the streets during the harsh Nordic winters. The strong presence of unions also makes sure that companies don’t fire people out of spite.

The layoffs didn’t happen, but that year we got a 0 Kr raise. Yes, that means we essentially got a pay cut considering inflation. But hey, it’s not like we were innovating. It was a great learning and growth opportunity.

Quit

That period of cost saving work eventually turned from a fun investigative work to a routine chase-and-kill mechanical chore. There was no sign of light at the end of the tunnel either. The company was stable at a level that it was comfortable with.

Growth and comfort do not coexist. — Ginni Rometty

Eventually I decided that I’ve had enough of FinOps and got a full-time position as a SRE at a global media company. Emil and Martin quit within a few months after me.

The story didn’t end bad though: the sites are still up and despite us three removing our salary burden from the company, we all got higher salaries offsetting the impact of the inflation on our own pocket! win-win!

Unsustainable

When the body is under stress, it goes into fight and flight mode. Adrenaline and cortisol increase the blood pressure to the muscles while limiting growth. It makes evolutionary sense. There’s no reason for the body to spend resources on growing your nails when you’re running from a tiger. Longer nails do not impact the tiger’s appetite! 🐅

When Sundar asks Googlers for "pausing development and re-deploying resources to higher priority areas", he’s sending clear stress signals. When he’s saying that new recruitment is limited to "engineering, technical and other critical roles", he’s talking about pumping blood into the muscles.

But this level of stress is not sustainable long term. Companies can only go so long in “war time” mode before the employees get exhausted and leave for a “peace time” company.

The final paragraph from Sundar’s memo is interesting:

Scarcity breeds clarity. It’s what drives focus and creativity that ultimately leads to better products that help people all over the world. That’s the opportunity in front of us today, and I’m excited for us to rise to the moment again.

Conclusion

We took the following steps to optimize for cost:

Reduce the consultant workforce and open an opportunity for the regular employees to fill in. You don’t need more people. You need clearer objectives. Give people mandate to execute the high-level cost-saving strategy.

Set up proper metrics in place to have a clear picture of the spending. You cannot improve what you don’t measure. For cloud costs, we set up observability metrics (read Are You Tracking the Right Metrics?)

Systematically start reducing costs from the most impactful to the least impactful (not from low hanging fruit). Approach the cost optimization like a product. This means a prioritization framework can come in handy.

Have an end in mind. “War time” has an expiration date and a cost to pay afterwards. It’s a bit like borrowing from the future growth of the company to fix the immediately burning fire.

This is my first post to Substack. I’ve been writing on Medium since 2015 and prior to that on Wordpress since 2012. If you like what you read, why not follow me on LinkedIn or subscribe here? I’m still trying to figure this thing out but I write about technical leadership, web architecture and JavaScript.

Update: Also read Layoffs Don't Tell the Whole Story