Emergent properties

What are nominal, weak and strong emergent properties and how to identify and mitigate their negative impact in system design?

Recently I posted about why reducing LLMs to “only predicting the next token” is a fallacy because if we ignore their emergent properties, we miss both their threats and opportunities.

The comments motivated me to write about the definition of emergence as someone who holds a MSc in interactive systems engineering, builds with AI, and specializes in resilience of sociotechnical systems (my book on the topic).

In this post you learn:

What are emergent properties and what kind of system has them?

What are weak and strong emergence as opposed to resultant properties?

How do emergent properties impact the reliability, maintainability, predictability, and cost of the system?

As usual, there’ll be plenty of examples and illustrations to make sure you can apply the learning in your technical leadership and engineering career.

Note: no generative AI is used to write, edit, or format this essay. (why?)

Reductionism

To understand emergent properties, we must first address the reductionist approach to engineering.

In simple words, reductionism is the belief that to understand a system, we only need to disassemble and analyze its parts then aggregate the results.

This approach works for the so called Resultant Properties (also known as Aggregate Properties).

For example:

The total weight of a car is the sum of the weights of its parts.

The storage capacity of a database is the sum of the data storage unites attached to it.

The latency of an API is the sum of the latencies of the chain of systems it depends on (we’ve covered the math behind serial and parallel dependencies in Composite SLO).

For resultant properties, we can safely use the [flawed but famous] quote:

The system is the sum of its parts.

This means analyzing at the micro-level (parts) can explain the behavior at the macro-level (system).

As we examined recently, the parts need to add to each other, not just fit.

Emergent Properties

The reductionist approach quickly falls apart when a property comes from the interactions and dependencies between the parts.

For example, the molecules that build living cells aren’t alive but together they create an organism that can consume energy, reproduce, and evolve.

If we pick a bucket of water, throw some coal in it and pour some liquid nitrogen over it, we have 99.1% of the atoms needed to build a human.

But is the secret sauce to make it alive, the “soul” if you will, the remaining 0.9% elements?! 😄 Of course not. Even if we arrange the atoms in cells, we still need the heart to pump the blood to keep those cells alive long enough to interact with each other.

An emergent property is a new, higher-level characteristic that cannot be predicted or understood by studying the parts in isolation.

Due to emergent properties, the correct saying is:

The system is the sum of the interactions between its parts.

Time and emergence

Interaction introduces the timing element.

Human brain can be described as neurons and synapses, but for a thought to emerge, it takes time for neurons to fire and trigger synapses.

A more accurate version of the statement would consider this timing aspect:

The system is the sum of the temporal interactions between its parts.

Not so memorable! 🫠 How about an image?

The temporal (time based) aspect is important because an key concern of systems engineering is to design systems that are predictable: we want to be able to reason about the system behavior in the future with an acceptable error margin.

It’s not enough to measure a property at the present, we need to be able to control its value in the future.

Emergence is subjective

You probably have seen those creative statues that look like “just a bunch of junk”. This is a quote directly from one YouTube video showing an example.

This work of art is designed backwards. Here’s an video (<5 minutes) about the process. It is optimized for the human cognition by humans.

Even though a mighty designer isn’t always necessary, as we’ll see LLMs are particularly designed to emit tokens that makes sense to us even though the exact process of inference may look like magic to the untrained eye, or we observe behavior that we haven’t specifically designed.

Although LLMs just generate tokens, but the cohesion and relation observed among those tokens creates meanings in our mind. As we’ll discuss, this is not accidental because they’re specifically trained to generate an output that makes sense to us.

There may be many emergent properties around us but we simply don’t have the capability to observe them (e.g. through our limited senses or devices) or make sense of them (e.g. through our limited and biased processing power).

These are collectively called unknown unknowns: we don’t even know how much we don’t know (read more in open prison theory).

The design of LLMs takes advantage of that perception and cognitive limit.

For example, by introducing an element of randomness (e.g., the temperature, topP, or topK parameters) they make the output even more interesting and “realistic”.

Is a pseudo-random generator an unknown unknown? Not really. But by definition it’s designed to appear random enough to screw with predictability.

Let’s acknowledge that:

Emergent properties can exist without necessarily being observable or understandable.

Emergent properties are subjective. They don’t break the [knowns or unknown] laws of the universe. Our limited perception and processing power makes them appear “magical” until they’re not.

There’s more to emergence however, as we’ll see. For example, they tend to appear when certain complexity thresholds are reached.

A typical characteristic of systems with emergent properties is multi-scale order:

There’s order at micro-level: neurons firing or tokens being generated.

There’s order at macro-level: thoughts, or AI-generated text, audio, image, or video.

The laws of scale don’t apply: the micro-level order is not present at the macro-level and vice versa.

We can make sense of the patterns we observe at both of these levels, but we cannot easily connect the two with deduction.

Note: there’s not always 2 levels. For example neurons are made of molecules and atoms which in turn are made of electrons, protons, and neutrons. Each of these levels are governed by known and mysterious rules.

Weak and Strong Emergent Properties

In biology the mesmerizing patterns that meets our eye from a flock of birds is used as an example of emergence.

As far as we can tell, no single bird decides how the shape of the flock changes over time. Yet the whole, as governed by a set of simple rules, shows the unpredictable blob animation.

How simple?

Reynold’s model, for example, has 3 rules:

Separation: Avoid crowding neighbors

Alignment: Steer towards average heading of neighbors

Cohesion: Steer towards average position of neighbors

Given enough data and processing power, this set of rules can create a simulation that looks pretty realistic. Here’s a web based simulation. Here’s another one you can tweak.

If we can simulate the emergent property, it’s called weak emergent property. Otherwise, it’s called strong emergent property.

“Weak” doesn’t mean useless. Weak emergent properties are much easier to model and define by a set of rules. This enables us to build a model that enables us to predict the future behavior of the system. But as the saying goes:

All models are wrong, but some are useful. —George Box

Unless they’re language models! Language models are always right! 🙃

Strong emergence on the other hand, is not easy to predict or understand. That’s because:

It has hidden variables that are beyond our available observation capabilities

It has too many variables that are beyond our processing capabilities

The good news is that LLMs can potentially stop having any emergent properties once we have the tools to observe and understand their magic.

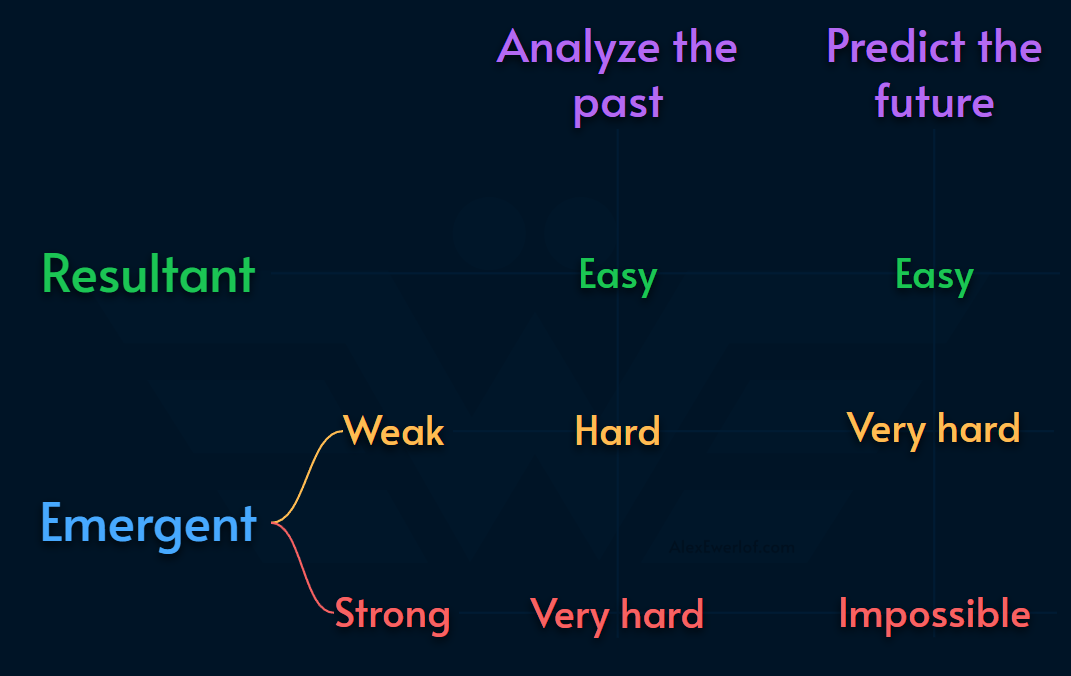

So why distinguish between strong and weak emergence? If we know what we’re dealing with, we can prepare accordingly.

Resultant properties are easy to reason about in retrospect and are relatively easy to predict in the future (simpler component failures cascading effect fall into this category)

Weak emergent properties are hard to reason about in retrospect and very tricky to predict in the future (many system incidents with multiple contributing factors fall into this category)

Strong emergent properties are almost impossible to reason about in retrospect and impossible to predict in the future (due to limitations of the observer and processing)

This is when it all ties back to resilience engineering and mitigation techniques: containerization, separation of concerns, circuit breakers, fallback, failover, …

System with emergent properties

Regardless of weak or strong, you should be looking for 5 characteristics in a system:

Non-Linearity: The output is disproportional to the input. A tiny trigger (e.g. single DNS config) causes a massive output (global outage, as we saw in the recent AWS incident). This non-linearity leads to “Phase Transitions” or tipping points that are hard to predict beforehand. As a rule of thumb all DSP (digital signal processing) systems as well as software system can show non-linear behavior. Analog systems, especially the linear ones, are less likely do accommodate “smart” logic where input and output are drastically unrecognizable.

Decentralized control: There is typically no central “brain” orchestrating the behavior. Order arises from local agents (Kubernetes master nodes, retrying clients, developer changing the code, users changing the data) following local rules without knowledge of the global state or concern for global order. The dynamics of local vs global optimization is at play.

Feedback loops: The system’s output feeds back into itself.

Positive Feedback: Amplifies deviation (e.g., Retry Storms and Thundering Herd).

Negative Feedback: Dampens deviation (e.g., Throttling may prevent a fix from propagating in a timely manner).

Multi-Scale order: The system exists on several distinct scales: the Micro (the interaction of parts) and the Macro (the pattern of the whole). These scales have a life of their own: we don’t go around thinking about our cells or gut bacteria, yet they’re very well alive and going through their own lifecycle impacting our feelings and thoughts. SoS (system of systems, where each part is also a system), is usually a fertile ground for emergent properties.

Openness: The system must constantly exchange energy/information to maintain structure. If you stop maintaining, entropy takes over. Code rot happens when little to no energy is spent in ensuring that the dependencies are up to date and the solution architecture evolves to fit the evolving problem it’s trying to solve.

There are some nuances in many such systems:

Memory: These systems typically remember their state because the state propagates (copies) to parts and can create side-effects. For example, after fixing the incident “root cause” the system doesn’t snap back to normal. The error may have propagated and changed the states that seem irrelevant but contribute to the confusion or “magical” appearance of the incident.

Latency: we mentioned the temporal interactions earlier. This means the state propagates across time, not always in predictable manners. The system may not have a consistent state at a given time. Consistency turns many properties to resultant properties which are much easier to reason about.

Downward causation: many engineers assume an “upward causation” where parts impact the whole (i.e., code → application → service). Emergent systems also have the opposite where the macro-state impacts the macro-state. For example, depression (a mental state) can have measurable effect in the body (e.g., hormonal imbalance, weaker immune system, etc.). These bidirectional causational relationships can reinforce or dampen each other (the feedback loops).

Operational independence: The components are not just parts; they are systems themselves with their own goals and local optimization. For example, a third-party API you depend on doesn’t care about your system’s survival. It optimizes for itself. SLOs and SLAs can help balance that conflict of interest. But at its core, such properties emerge at the intersection of local optimization (the API provider’s velocity) vs global optimization (your product’s stability and reliability). Sometimes, this attribute is desired (loose coupling, separation of concerns), but we need to be aware of the emerging side effects.

Observer effect: what looks like “magic” (strong emergence) is often just computational irreducibility (weak emergence). We just haven’t been able to find all the hidden variables, or have an algorithm to simulate it, or enough compute power to do so.

The primary difference between weak and strong emergent properties is operational (can we predict future?), not theoretical (can we explain the past?)

OK, I feel like I pushed you really hard. 😅 Let me know in the comments if this section was too technical or did you find it useful.

Emergent incidents

Incidents are a good source of understanding system properties as they are implemented and run, not as they are designed:

Resultant: If the incident was simple and straightforward with no cascading consequences, there’s probably a resultant property at play. Example: logs consumed the available disk space and this broke the operating system’s swap memory causing the app to crash! These incidents usually have one root causes often the blast radius is contained within one part of the system (e.g. the pod is killed and recreated).

Emergent: If you could not predict the contributing factors, you’re likely dealing with emergent properties that only show up when the system is put together.

Weakly Emergent: If you can successfully trace the incident back to contributing factors in a way that you can replicate the incident and prevent it in the future, you have found a weakly emergent property of the system. For example: the autoscaler in front of a payment API hits a hard limit that was put there for cost saving and fraud prevention but it brings the customer support system down because recently an MCP was introduced that blocks the non-AI part of the system.

Strongly Emergent: If you can’t successfully trace the incident back to contributing factors, there’s probably strong emergence at play. Example: a Chat bot starts tweeting inappropriately (Microsoft Tay) or your coding assistant decides to delete the database (Claude). Can this be explained by going through all training data? Probably… not! 🚫 For LLMs specifically, this is a topic of speculation. For example, you can work around safety guard rails by distracting the model’s attention mechanism with poetry or encoding. Even a small fine tuning can create massively misaligned models (the non-linear attribute). LLMs are notoriously hard to train, secure, and align but that doesn’t mean all of their properties are strongly emergent.

A single system can have all 3 types of properties.

As a mental exercise, think about a system you know very well and see which properties are resultant, weakly emergent and strongly emergent.

In safety engineering (SEBoK), “strong emergence” is often used to describe catastrophic failures that were fundamentally unpredictable during design because the system’s operational independence creates novel autonomous failure modes.

The primary difference between weak and strong emergent properties is the ability to practically simulate and replicate them (computational reducibility) to predict and control system behavior, not just the ability to explain or justify them.

The difference is operational (can we predict future?), not theoretical (can we explain the past?).

Not all emergent properties lead to incidents though. AlfaGo beat the world’s Go champion using the famously new move 37.

This is a fascinating free documentary (1.5 hours by Google DeepMind) about Demis Hassabis, AlfaGo, and AlfaFold (among other things).

The reason incidents are particularly interesting for understanding emergent behavior is because they’re surprising, expensive, and enjoy real incentives to learn from them to make sure they don’t happen again.

Emergence in LLMs

Back to where we started, but hopefully with a richer vocabulary and wider toolbox.

Do LLMs have emergent properties or not?

LLMs widely vary in architecture, size, modalities, tools, “thinking”, and training data.

It is true that they generate tokens (observable output), but as SoS (system of systems) they have many aspects that make emergent properties possible:

Non-Linearity: mimicking our brain structure at the micro-level, NN (neural networks) use activation functions which are non-linear. This means a small tweak in the input (prompt tokens) can widely change the output (e.g. chat completion, code generation, or multimedia output).

“Memory”: The ability to focus attention on part of the context (attention is all you need) is a fundamental idea behind the current generation of LLMs. On top of that, many models are paired with memory to remember context from previous conversations or techniques like RAG or CAG.

Downward causation: the attention mechanism considers both the current output (even with KV cache), context window, and previous training to predict the most likely token. However, there’s an element of randomness (

temperature,top-p,top-k) that makes these calculations non deterministic. In fact there’s a $50 billion startup (founded by ex-CTO of open AI) to tackle that. When the part (token) is unpredictable, it also makes the whole (the response, the “thinking”) unpredictable and vice versa (due to the feedback loop between tokens).Operational independence: MoE (mixture of experts) is an LLM architecture that relies on a router to selectively activate a subset of experts. And these experts have different concerns while interacting with each other.

Observer effect: through RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) these models are trained to mimic a human-looking response. That’s the “magic” part and although theoretically we should be able to explain how the human feedback impacts a certain output at a macro and micro level, this task is computationally expensive at the scale of the models we use every day (billions of parameters). Among big AI vendors Anthropic’s blog is the best source of this sense making exercise.

Openness: theoretically, a freshly trained LLM can be a closed system that is only impacted by its training data. But due to the sheer size of the input, it’s practically impossible to vet all the sources. As Anthropic demonstrated recently as few as 250 malicious documents can corrupt a model and produce a backdoor.

Anna Rogers mentions, there are 4 ways people define emergence, none of which is exactly how we defined it:

A property that a model exhibits despite not being explicitly trained for it.

A property that the model learned from the training data.

A property that is not present in smaller models but is present in larger models.

A property that appears at random and on unforeseeable model scales.

When we say emergence in the context of systems engineering and resilience architecture, we’re mostly interested to the practical implications (prediction, prevention) not the theoretical or philosophical rabbit hole (cause honestly it’s endless).

The good news is that LLMs can potentially stop having any emergent properties once we have the tools to observe and understand their magic. When that day comes, they’re as predictable as a spellchecker, but until then, emergence it is. 😄

Pro-Tips

So what can you do with this information?

Know your system: if it can expose emergent properties, you need to take measures to detect, contain, and dampen the negative effects. Fortunately, there are no shortage of resilient architectural patterns. Just google “well architected [INSERT YOUR CLOUD PROVIDER]” or read my book which talks about both the human side and the technical side (Reliability Engineering Mindset)

Acknowledge the limitations in observation and processing capacity that differentiates resultant properties from emergent properties. Instead of getting stuck in the philosophical discussion, our engineering angle on emergence is primarily focused on their utility to:

Make sense of the past system behavior

Predict the future system behavior.

For LLMs specifically, instead of debating whether a specific property is emergent or not, we can look at the ability of creators of SOTA (state of the art) models to control their behavior. Alignment still remains the biggest challenge for AI and until that’s solved, my money is on LLMs having emergent properties. This means we cannot reliably predict the future system behavior or control it because we cannot measure or understand all the variables that contribute to the state or behavior.

Personally, I use a IOC (inversion of control) pattern where a deterministic code controls the workflow reliably while LLM is used for HCI (human-computer interaction: input and output) or generation (e.g. images, stories, etc.). You can see an example of that in the pre-prod version of SLC (Service Level Calculator).

The IOC workflow is in contrast with agentic or vibe-* approach where we naïvely give full control to the LLM and hope that it follows specs to the dot. That was my main counter argument against a special dialect of spec-driven development that treats code as disposable build artifact.

My monetization strategy is to give away most content for free but hese posts take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to draft, edit, research, illustrate, and publish. I pull these hours from my private time, vacation days and weekends. The simplest way to support this work is to like, subscribe and share it. If you really want to support me lifting our community, you can consider a paid subscription. If you want to save, you can get 20% off via this link. As a token of appreciation, subscribers get full access to the Pro-Tips sections and my online book Reliability Engineering Mindset. Your contribution also funds my open-source products like Service Level Calculator. You can also invite your friends to gain free access.

And to those of you who support me already, thank you for sponsoring this content for the others. 🙌 If you have questions or feedback, or you want me to dig deeper into something, please let me know in the comments.

Further reading

Professor Simon Prince: This is why Deep Learning is really weird, YouTube, Dec 2023

Emergent Abilities in Large Language Models: An Explainer, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University, April 2024

Large Language Models’ Emergent Abilities Are a Mirage, Wired, March 2024

A Sanity Check on ‘Emergent Properties’ in Large Language Models, Dr Anna Rogers, July 2024

Prof. David Krakauer: Can Outsourcing Thinking Make Us Dumber?, YouTube, July 2025

This was a fantastic deep-dive, Alex — especially the distinction between weak vs. strong emergence as an operational question (“can we predict it?”) rather than a philosophical one. The connection to real-world incident analysis really lands: most engineering surprises are weak emergence in disguise, and having the vocabulary to spot it makes all the difference.

Loved the practical framing too — especially the reminder that resilience patterns (circuit breakers, isolation, SoS thinking, IOC) are essentially guardrails for when unpredictability is a feature of the system, not a bug. Great read!