SLA stands for Service Level Agreement. Its primary purpose is to communicate a reliability guarantee towards external service consumers.

This post uses illustrations and examples to:

Define SLA in relation to SLI and SLO

The 3 conditions that must be met to have an SLA

Structure of an SLA document (how to read or write it)

We then close with comparing how SLA is used in SRE vs ITIL.

The basics

SLA builds on top of what we have already covered:

SLI: Service Level Indicator → these are just metrics that show how the service consumer perceives reliability of our service (not to be confused with microservice or a backend, in Service Level model, a service refers to a capability or solution for a customer problem).

SLS: Service Level Status → is the actual value of the indicator in a given time period. If SLI specifies the formula, SLS puts the actual values in it to quantify the reliability and performance of the service.

SLO: Service Level Objective → these set the targets for those metrics in a period of time (like 30 days). More specifically, what’s the acceptable percentage of good events or timeslots in a given period?

SLA: Service Level Agreement → these are legal agreements typically with financial consequences. This is often the source of confusion and the main reason this article exists.

In other words, SLA contains SLI and SLO.

SLA in the context of SRE

Here is how Google SRE book defines it:

… SLAs are service level agreements: an explicit or implicit contract with your users that includes consequences of meeting (or missing) the SLOs they contain.

The agreement aspect of SLA refers to a legally binding contract not just a handshake between teams (that’s where an internal SLO usually stops).

To reduce ambiguity, the book offers a simple litmus test:

An easy way to tell the difference between an [internal] SLO and an SLA is to ask "what happens if the SLOs aren’t met?": if there is no explicit consequence, then you are almost certainly looking at an SLO.

And here is an example to solidify the difference:

Google Search is an example of an important service that doesn’t have an SLA for the public: we want everyone to use Search as fluidly and efficiently as possible, but we haven’t signed a contract with the whole world. Even so, there are still consequences if Search isn’t available—unavailability results in a hit to our reputation, as well as a drop in advertising revenue. Many other Google services, such as Google for Work, do have explicit SLAs with their users. Whether or not a particular service has an SLA, it’s valuable to define SLIs and SLOs and use them to manage the service”

SLA is a legal layer on top of a high level SLI and a more serious SLO.

In SRE fundamentals, Google Cloud PMs Jay Judkowitz and Mark Carter mention:

At Google, we distinguish between an SLO and a Service-Level Agreement (SLA). An SLA normally involves a promise to someone using your service that its availability SLO should meet a certain level over a certain period, and if it fails to do so then some kind of penalty will be paid.

This might be a partial refund of the service subscription fee paid by customers for that period, or additional subscription time added for free. The concept is that going out of SLO is going to hurt the service team, so they will push hard to stay within SLO.

If you’re charging your customers money, you will probably need an SLA.

The purpose of the SLA is to build trust with key service consumers and stakeholders. It shows that the service provider is serious enough to compensate for a service disruption. 🤑 SLA provides consumers with leverage to hold the service provider accountable for service degradation. 🔨

Not every consumer has an SLA though.

Google Search is an example of an important service that doesn’t have an SLA for the public: we want everyone to use Search as fluidly and efficiently as possible, but we haven’t signed a contract with the entire world. […] Many other Google services, such as Google for Work, do have explicit SLAs with their users. — Google SRE Book, Chapter 4

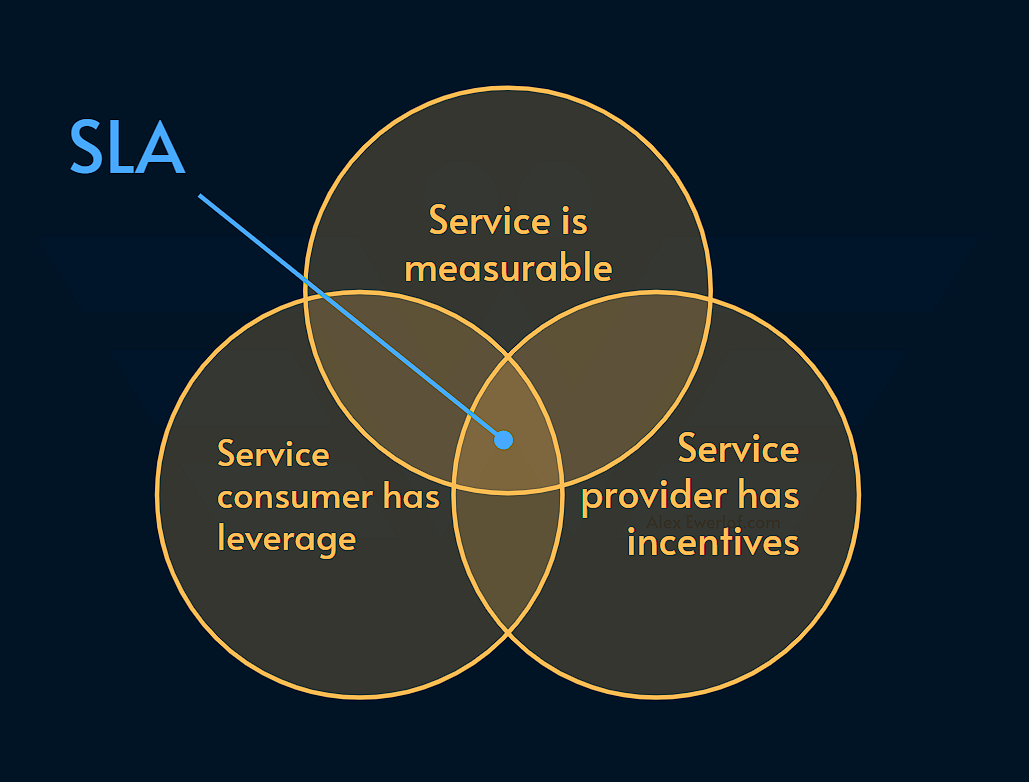

Requirements of SLA

SLA only makes sense when all 3 conditions below are met:

Measurability: service level is quantifiable (SLI) to build a model about how the service is going to be consumed

Leverage: the service consumer has leverage to hold the service provider legally accountable for breaching the contract.

Incentives: the service provider has a motivation to guarantee the service level.

Example

Let’s imagine you are a company that sells customer service chat bots. You’ve built your chat bots on top of an external cloud infrastructure provider.

Obviously, you want the infrastructure to work all the time because if the infra goes down, your chat bot is not available and it’s bad for your business. But as we argued before 100% service level is unrealistic. With SLA, you get some sort of guarantee because if the infrastructure goes down, the provider must compensate you.

SLA allows sharing risk between the service consumer and service provider.

However, beware that most service providers cannot act as an insurance provider — otherwise their fees would be too high to be competitive!

What the service providers are willing to put on the table in terms of penalties is often much less than the money you lose when your service goes down.

Your business must have a higher revenue to be able to afford the external cloud provider services (except when it’s a startup but even then, you must think about the risks). When they go down, they may give back part of what you pay them, but they definitely don’t compensate your entire loss.

If they had to compensate for every business loss for every type of business model that runs on their cloud, they’d go out of business very soon!

Structure of the SLA document

The purpose of the SLA document is to set the expectations for external parties about:

DoS (definition of service): What is the service

SLI: How does service provider measure their commitment?

SLOs: What level of reliability does the service provider commit to?

Penalties: What are the penalties and incentives? (usually formatted in a table that corelates credits to error budget)

Exclusions: What is the intended consumption and what is excluded from the agreement?

Enforcement mechanism: What are the support channels and requirements for the service consumer to apply those penalties and incentives?

Glossary: A glossary of terms is usually added for clarity including the “fine print”.

Most SLAs follow that exact structure. A few examples:

Sometimes a company can make a special deal with a customer on top of an MSA (master subscription agreement). Examples here: Datadog, Zendesk, Salesforce.

Traditional service providers usually offer a Terms & Condition or Terms of Service instead of SLA. As we discussed before one of the key ideas behind service levels is to shift the conversation from “the systems should never fail”, to “what is failure and how much of it can you tolerate”. Besides, quantified service levels allow informed discussions about cost of reliability among other things.

SLA vs SLO

SLA has an SLO. We call that an external SLO.

The organization that owns the service, has internal SLOs as well. In a separate article, we’ve touched on the difference between the two in various aspects:

SLA: ITIL vs SRE

The Information Technology Infrastructure Library, or ITIL, is a set of processes for IT activities, such as IT service management (ITSM) detailed in a few core books with thousands of pages on how to build and run IT services complete with certificates.

ITIL follows a more traditional, process-driven approach to service management with formal documentation and hierarchical structures. SRE on the other hand promotes a culture of collaboration between development and operations teams.

Not every enterprise uses ITIL and the ones which do, may implement their own flavor.

If you do have some level of ITIL adoption in your organization, then be prepared for there to be substantial overlap between SRE and ITIL practice. One such difference is SLA.

SLO takes the center stage in SRE while SLA is primarily used to communicate consequences of breaching the SLO to external service consumers with leverage (e.g. paying customers). SREs typically don’t decide the business consequences of SLA alone.

ITIL practitioners treat SLAs as comprehensive documents covering multiple aspects of service delivery, with detailed specifications for various service parameters.

ITIL integrates SLAs deeply into the service design process, while SRE views them as business agreements that engineering teams help fulfill (but don't typically “design”).

The concept of error budgets is not traditionally emphasized in ITIL's approach to SLAs whereas in SRE, it’s a core tool for risk control and balance reliability with innovation.

These different approaches reflect the broader philosophical differences between ITIL's process-oriented service management framework and SRE's engineering-focused approach to reliability.

My monetization strategy is to give away most content for free. These posts take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to draft, edit, research, illustrate, and publish. I pull these hours from my private time, vacation days and weekends. The simplest way to support this work is to like, subscribe and share it. If you really want to support me lifting our community, you can consider a paid subscription. If you want to save money, you can get 20% off via this link. As a token of appreciation, subscribers get full access to the Pro-Tips sections and my online book Reliability Engineering Mindset. Your contribution also funds my open-source products like Service Level Calculator. You can also invite your friends to gain free access.

And to those of you who support me already, thank you for sponsoring this content for the others. 🙌 If you have questions or feedback, or you want me to dig deeper into something, please let me know in the comments.

Hej!

Thinking about SLAs they can feel quite strict to me (disclaimer: I never defined SLAs in my work but SLOs). Personally, SLO hold teams accountable, they also allow for some flexibility in reaching those goals and even changing the threshold because they are internal agreements.

Speaking of SLAs, how much experience have you had with adjusting them? Recent changes within the company, like the layoffs, might make some existing SLAs unrealistic. What are your thoughts on how we can approach these situations?

One other thing that piqued my curiosity: Have you ever worked on building cascading SLOs/SLAs? For instance, how would we define our own service level if a third-party service we depend on only offers 90% availability?

Thanks as always for your insights!

Such a great article, thanks for sharing! I love how related concepts are collected in the same post, especially with real-life examples from BigTech (and others).