“I want all teams to set SLAs between each other”, said the leadership.

💭 And I thought to myself: “What are you smoking? I want some of that too! It must be good! What do you mean SLA between teams? Unless one team is literally paying the salary of another team and can take them to court in case of a breach, we’re talking about SLO, not SLA”!

SLA = Service Level Agreement

SLO = Service Level Objective

To the untrained eye, the difference is very subtle: just one vowel! Many people, including self-proclaimed SREs use SLA and SLO interchangeably.

🧐 But once you know the difference, statements like the one I quoted becomes ridiculously funny.

When I’m hiring SREs, asking the difference between SLA and SLO is my favorite “trick question” because it reveals nuanced knowledge about how reliability is communicated.

This short post covers:

Why does this distinction matter?

An illustration to build a memorable base

Quotes from Google’s books

This is not an entry article about SLA or SLO. We have covered those topics before:

As usual, there will be plenty of examples and illustrations to make the abstract topics more approachable.

Why does this post exist?

I really didn’t want to write this post because Google SRE books have done a great job of explaining it. But for 2 reasons I have to:

If the point of the language is to communicate, it really pays back to use the correct word. Normally, I wouldn’t care —I’m not a word Nazi. But when building a user facing service, knowing the difference and relationship between SLA and SLO pays back enormously.

Asking “AI” and searching the internet gets you only so far. Atlassian, PagerDuty, and even Google have pages on the topic but I still haven’t found a resource that is crisp, illustrated, and to the point. I needed something that I could share with people without having to repeat myself again and again. This post exists to scale that ensuing “Aha” moment.

A visual guide

Sometimes SLI is brought up in comparison to SLA and SLO. We have covered each of them in separate articles.

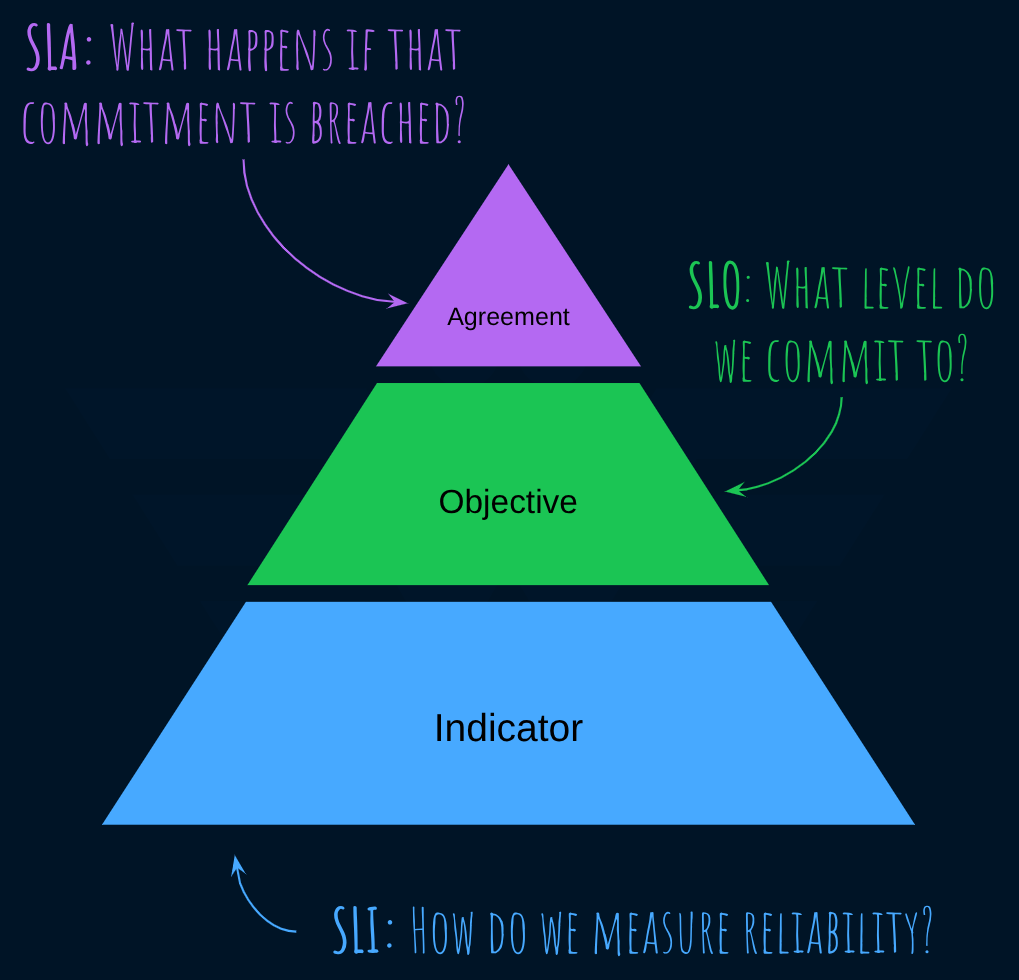

In simple terms:

SLI: Service Level Indicator → these are just metrics that show how the service consumer perceives reliability of our service (not to be confused with microservice or a backend, in Service Level model, a service refers to a capability or solution for a customer problem).

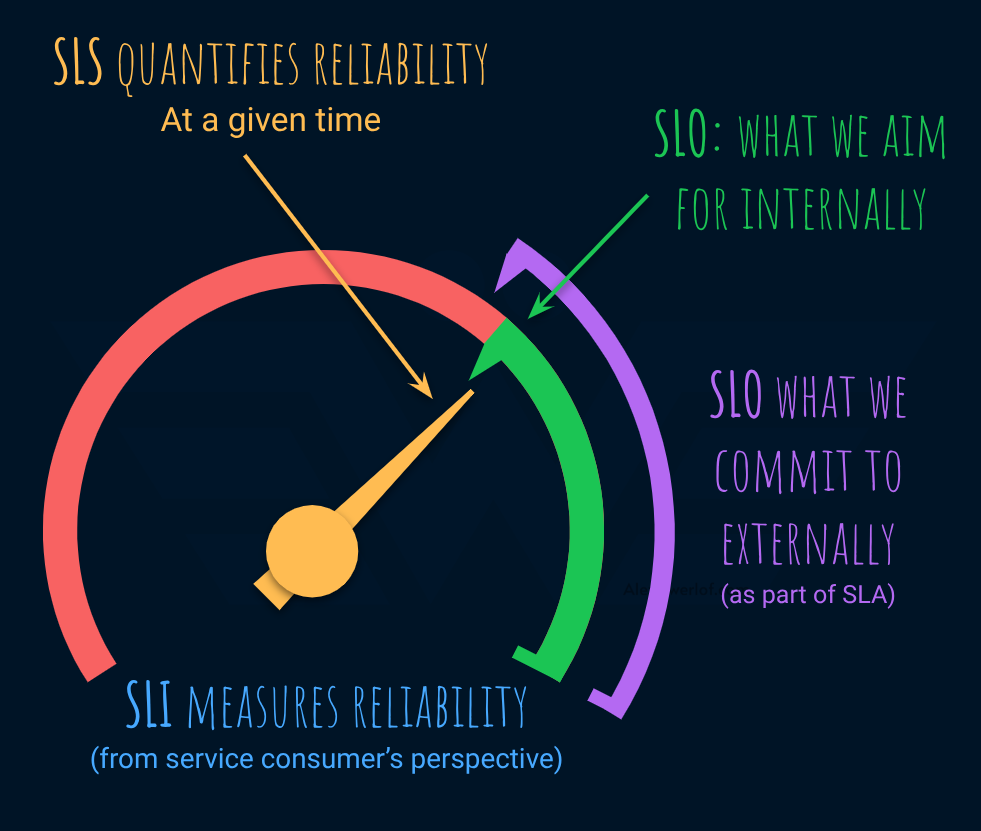

SLS: Service Level Status → is the actual value of the indicator in a given time period. If SLI specifies the metric and formula, SLS puts the actual values in it to quantify the reliability and performance of the service.

SLO: Service Level Objective → sets the targets for those metrics in a period of time (like 30 days). As long as SLS is above SLO, we’re good.

SLA: Service Level Agreement → is a legal agreement that connects an external-facing SLI and SLO to financial or legal consequences. This is often the source of confusion and the main reason this article exists.

Here’s a visual representation using a gauge as a metaphor for SLI:

It can be a bit confusing because SLA has an SLI and SLO. The best way to think about SLA is as a legal layer on top of SLI and SLO.

What does Google say?

We get our first clue in Chapter 4 of Google SRE Book:

… [SLA is] an explicit or implicit contract with your users that includes consequences of meeting (or missing) the SLOs they contain.

More explicitly, the difference is in the consequence:

The consequences are most easily recognized when they are financial—a rebate or a penalty.

To reduce ambiguity, the book offers a simple mental exercise:

An easy way to tell the difference between an SLO and an SLA is to ask, "what happens if the SLOs aren’t met?": if there is no explicit consequence, then you are almost certainly looking at an SLO.

And here is an example to solidify the difference:

Google Search is an example of an important service that doesn’t have an SLA for the public: we want everyone to use Search as fluidly and efficiently as possible, but we haven’t signed a contract with the whole world.

Even so, there are still consequences if Search isn’t available—unavailability results in a hit to our reputation, as well as a drop in advertising revenue.

Many other Google services, such as Google for Work, do have explicit SLAs with their users. Whether or not a particular service has an SLA, it’s valuable to define SLIs and SLOs and use them to manage the service”

SLA/SLO in my experience

There are quite a few pages on the internet about SLA: Wikipedia, Amazon, IBM, Atlassian, SalesForce, ZenDesk, …

Apart from the fact that some of them parrot each other, the Google SRE book remains the undisputable reference. Even then, having helped hundreds of teams to set their SLO and consulted multiple SLAs, I’m opinionated about a few aspects:

SLA should be a written legal contract. Google’s definition gives implicit contracts a pass (e.g. if you say something in a meeting, email, or API documentation), but in my experience SLA is important enough to write a legally binding contract to remove any confusion or interpretation.

SLA should be explicit and external-facing. Google does a good job clarifying why SLA is external facing but it’s not overly prescriptive about what it actually means. To me, any entity that sells a service should have an SLA that is easy to find and understand. When you buy a pair of speakers online, you check the specifications to know what you’re getting for the money. The same is true for more complex SaaS: as a paying consumer, you have the right to know what level of reliability you’re buying, how much you can depend on it, and what happens if you don’t. Having an SLA is not just goodwill. It can protect the service provider from law suits due to misunderstanding and misalignment of expectations.

The confusion between SLA and SLO mainly stems from 2 anti-patterns:

SLO’s that are disconnected from accountability and change management. Some organizations which are at the beginning of their journey to adopt SLOs, only see them as a way to measure and optimize service level. This only utilizes half of their advantage.

A good SLO is tied to accountability via alerting. If the service is degrading or disrupting, you want the service owners to be on top of it. Only when the SLO is connected to alerting, it can be taken seriously.

The complement of SLO, Error budget, should also be connected to CI/CD to block non-urgent changes. If the service has burned its error budget, change (as the number 1 enemy of reliability) should be blocked in order to stick to the level of commitment made by the SLO. Only when the error budget is used to control risk, it can be taken seriously.

SLA’s are not seen as external facing legal documents. This comes from poor understanding of the legal side of the SLA. This is sometimes due to how other frameworks like ITIL use SLA loosely for service design.

When the SLO is connected to alerting and change management, it has enough consequences to guide the engineers own their service.

You don’t need to call it an SLA to distinguish serious SLOs from others. If it’s not serious, it shouldn’t be an objective in the first place.

The word “agreement” is primarily and exclusively reserved for a legal agreement based on my experience.

The SLA takes much more effort and uses a completely different bag of tricks to protect the service provider from the risks of the service consumer.

In a future article, we’ll unpack this bag of tricks for both when you’re offerring a SLA or when signing a SLA provided to you. What’s important is to understand that SLA is a completely different beast with different incentives, participants, and guarantees.

Similarities and differences between SLA vs SLO

SLA and SLO are related but different:

Accountability

Previously we’ve covered the difference between accountability and responsibility.

TLDR; it boils down to legal consequences and punishment.

Similarity: Both SLA and SLO communicate measurable service level commitments towards the service consumers.

SLA: the commitment is typically tied to some financial penalties and entitles the consumer to compensation or legal action in case of a breach.

SLO: is softer and the consequence of burning the error budget is typically implemented in annoyances like not being able to push new changes to production (change is the number one enemy of reliability: any time you change a system, its likelihood of failure spikes up).

This difference is small but important because as we discussed in the article about SLA, it boils down to service consumers having leverage or not.

SLO Target

They both set expectations that are set through research and negotiation.

An SLO that is in the SLA promises less reliability than internal SLO because our external commitment should always be lower than what we internally aim for.

For example, if internally we aim for a SLO of 99.99%, the SLA we commit externally may be 99.5% (roughly buying us twice the error budget).

Under promise and overdeliver, not the other way around.

Regardless of what we aim for, it is always advised to think about the cost of reliability and balance that against the business profit (revenue - expenses) for a given service.

This is the core premise of the 10x/9 rule which elaborates “those 9’s aren’t free!” 😃

Audience

Similarity: they both set expectations between a service provider and service consumer.

SLA: the consumer is often an external entity with leverage.

SLO: the consumer is often internal (e.g., other teams in the same organization).

Level of detail

Similarity: They both tie an indicator (metric) to an objective (e.g. 99.9%) but are detailed in different ways.

External SLIs that are tied to SLA are usually simpler (availability is the most common one). However, SLA has extra details about the legal aspect (consequences, compensations, exceptions, credit, support mechanisms) and typically contains a glossary to build a common language with external consumers. If the service provider is a large vendor, it may get away with having a cookie cutter SLA for all consumers (see Google Cloud SLA for an example).

Internal SLIs that are only tied to SLOs are more detailed because their primary target are the engineering teams which have a good knowledge about how the service is implemented and consumed. This leads to more nuanced and detailed SLIs that focus on what the team controls. In contrast, external SLIs abstract away the shape of the organization and implementation details.

Monitoring

Similarity: They are both monitored and tied to alerting.

The SLS of an SLA: may also be tied to a publicly visible status page to help the consumers troubleshoot their system by quickly assessing the reliability of their dependencies. When things fail, the consumers should have an effortless way to answer: “is it me or is it them?” For example, the Azure Status page helps their customers to roll out cloud disturbances in case they have an incident. Same with Github, Slack, Google and a whole bunch of others. There are tons of products in this area, and you can even set one up using open-source products like Cachet.

The SLS of an internal SLO typically misses that public-facing monitoring and is often implemented as an internal dashboard on the observability platform. It requires less effort.

Purpose

Similarity: They are both used to set expectations.

SLA is written in a way that protects the service providers’ interest. That is because when the service is disrupted or degraded, the service provider already looks bad. The last thing it needs is to add insult to the injury and put money on the table.

Internal SLO is primarily used for giving a focus to service optimization.

… if you can’t ever win a conversation about priorities by quoting a particular SLO, it’s probably not worth having that SLO —Google SRE book Chapter 4

Revision frequency

Similarity: both are subjected to revision and readjustments as the tech evolves and/or the consumer demands changes.

SLA: is revised less often and is more ceremonial because it involves business stakeholders, legal, and representatives from different parties.

Internal SLO: can be revised every few months, sometimes weeks. Since its primary consumers are the internal engineers, it may go through rapid evolution to become what makes sense to them. Moreover, the internal stakeholders typically enjoy more flexibility than an external stakeholder to get what they want in a timely manner.

My monetization strategy is to give away most content for free. These posts take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to draft, edit, research, illustrate, and publish. I pull these hours from my private time, vacation days and weekends. The simplest way to support this work is to like, subscribe and share it. If you really want to support me lifting our community, you can consider a paid subscription. If you want to save money, you can get 20% off via this link. As a token of appreciation, subscribers get full access to the Pro-Tips sections and my online book Reliability Engineering Mindset. Your contribution also funds my open-source products like Service Level Calculator. You can also invite your friends to gain free access.

And to those of you who support me already, thank you for sponsoring this content for the others. 🙌 If you have questions or feedback, or you want me to dig deeper into something, please let me know in the comments.

I’ve had teams set agreements with each other that specify the consequences if the error budget is depleted. It seemed like it fit the definition of an SLA in principle, but not a legal agreement as defined by this article. In fact, you referenced one of the consequences we used- no features deployed until x,y,z. In which of these acronyms would you classify that? Ok to use SLA? Or is the legal part strict?

SLO is wrong definition for OLA.