Service Level Terminology

Service, Provider, Consumer, Task, Stakeholder, Owner, Failure, Metric, SLI, SLO, SLA, error budget, alerts, ...

In the context of service levels, there are multiple terms that are related to each other. This post serves as a glossary to define and connect:

Service, its provider, and owner

Consumer, its tasks, and how failure can impact it

Metric, indicator (SLI), status (SLS), objective (SLO), legal agreements (SLA)

Using alerting and error budgets to control risk

As usual, we’ll be using visuals and examples to nail the topics.

Overview

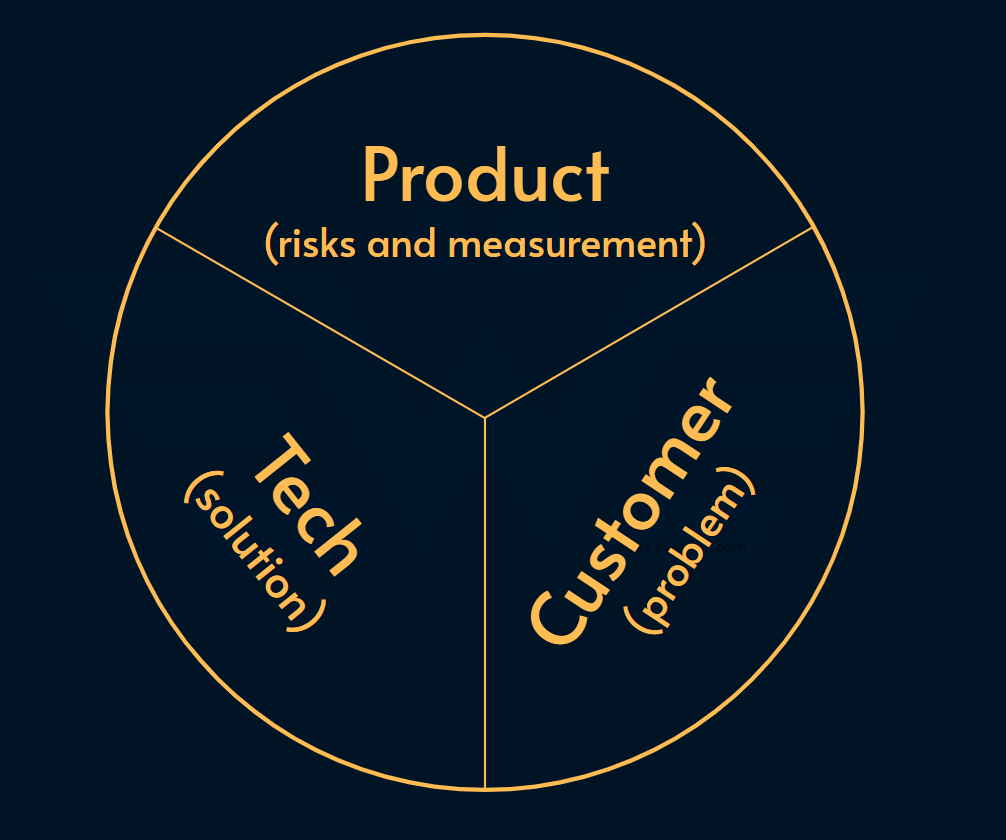

At the very high level, a product is about solving a problem for some customers.

So on one side, we have the tech stack that solves a problem.

On the other side, we have the customers who have some needs or problems to solve.

The success of the product depends taking calculated risks to bet the services it offers. And good decisions need good data. We need to measure how good those services are performing to help the customers do their tasks.

Put it on a diagram and we get this:

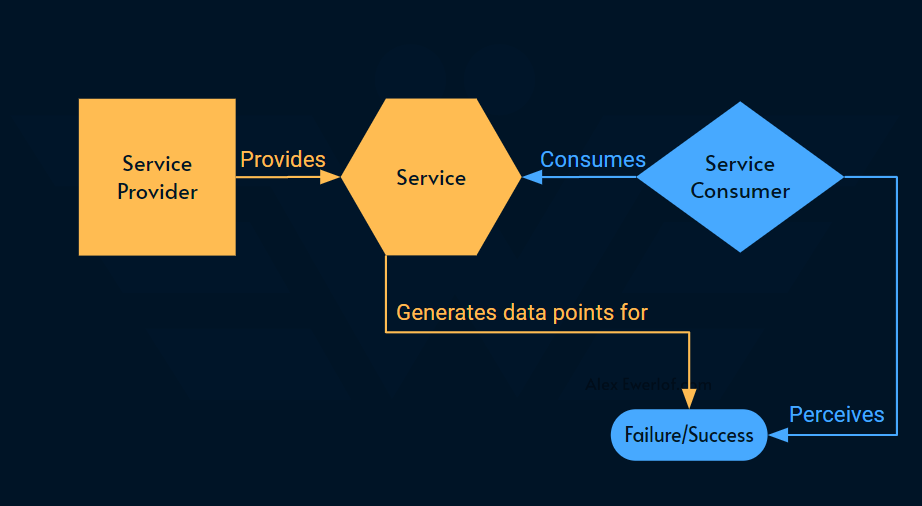

Think of a product as a group of services, each catering towards some tasks for the user.

And that’s where Service Levels come in. It measures the service to provide insights for business decisions that evolve the product.

There’s more to that, and I dissect that in my online book:

Service levels help set expectations between service provider and consumer.

Service levels help implement ownership and give a direction to organization design.

Service levels help balance risks and optimize what matters.

Let’s first build a solid foundation before going into details.

Service

This is the trickiest term in the whole glossary. Too often I see the teams confuse service (in the context of service levels) with service in other contexts like in Kubernetes, microservice architecture, or AWS.

They’re not wrong. That’s just how languages work. A give word can have different meanings in different contexts.

In the context of service levels, a service is an abstract concept. A piece of tech provides the service (hence called service provider), but the service itself is just the ability to solve a problem for the consumer.

Due to common misconceptions, there is a dedicated article about the service.

Service can be any of these 3 types:

Automated: a service that’s fully automated using software/hardware. For example an endpoint that allows searching book titles and fetching book metadata to render a page in an online book store.

Manual: a manual service is either too expensive to automate (in terms of money, complexity, etc.) or requires human intervention or judgement (for example due to compliance, and ambiguity that requires flexibility). For example governance, incident triage, or customer support. Manual services are provided by a group of people.

Hybrid: a mix of the two. For example, the infrastructure team may use IaC (infrastructure as code) to govern access to a 3rd party tool (service). They expect the developers who use the platform (consumers) to create a PR (pull request) with their user-id in the IaC repo. The infrastructure team may manually review the PR. Once the PR is merged, it grants/removes access to that 3rd party tool using GitHub Actions automation.

Provider

Service provider is the entity that provides the service.

If you’re familiar with SAML, you may recognize the term. The service provider is usually a system or component (using Backstage’s terminology) but it can also be a group of people (for manual services):

Components: are concrete pieces of technical solution that solve a problem for the service consumer. For example: a microservice, a database, an API gateway, a piece of hardware, a 3rd party or open source piece of software. Components can sometimes be deployed independently. For example a single “service” in a microservice architecture, can be thought of as a service provider of type component.

Systems: are logical grouping of multiple components. For example, an complex microservice architecture that is owned by one service owner can be considered a service provider of type system. Think of systems as folders that contain components as files. In the context of service levels, using system for a service provider creates a more abstract view which has its cons and pros. On the plus side, the abstraction

Group: are people who provide manual services that are either too expensive to automate or require human intervention or judgement. For example governance, incident triage, or customer support. The point of measuring service levels for manual services is to quantify performance in order to optimize. This data can also help justify automation when it is worth the ROI (Return On Investment).

Note: We use a terminology that is roughly based on Backstage. Backstage is a CNCF open source product for building Internal Developer Portals (IDP). Backstage terminology is roughly based on the C4 model. There are a few differences between our terminology and Backstage:

In Backstage, Components only provide APIs whereas in our terminology, Components provide any Service regardless of the technology or mechanism that’s used to expose that service. i.e., a component can provide a service that is a GUI (Graphical User Interface) or AUI (Audio User Interface) as well as API like gRPC, REST, or WebSocket.

In our terminology, the Group (people) and System (logical grouping) can also provide services whereas in Backstage, only components expose an API.

Owner

Service owner, owns the service. We’ve previously established the meaning of true ownership. In the context of service level it means:

Knowledge: Service owner knows how the service works, and how its performance is measured by service level indicator (SLI)

Responsibility: Service owner is held responsible for maintaining the service level above the objective that was agreed upon (SLO). The basic form of implementing this responsibility is to be on-call for the commitment (alerting on SLO will be discussed in another post). If there’s a legal agreement in place (SLA), service owner is accountable for that.

Mandate: Service owner has full control over HOW the service solves the consumer’s problem. This means they have access to all the knobs and gauges to optimize the service they are responsible for and don’t have to beg another party for permission to improve their service level. (this “begging” part is typically a symptom of broken ownership)

Ideally the service owner has all 3 elements of ownership. But the owner is at least responsible for the service meaning if there’s an issue with the service level, the owner is supposed to own that failure and do something about it.

Service owner is typically a group because people own the service. That group can be any organization unit:

An individual who maintains the service and is responsible to improve it

A team: that does the same. For example an internal PaaS (Platform as a Service) team offering an internal platform, or a front-end team behind the website that allows customers to order books, or a IoT (internet of things) team that allows the mobile app team to communicate with devices.

Or a corporation which sells the service. For example a SaaS (software as a service) to solve a particular problem (Example: Adobe) or a Platform for serving content (Example: Substack, YouTube) or software services (Example: Redhat). When money is involved, there’s typically a Service Level Agreement (SLA) in place too.

When a service is manual or hybrid, the service provider and owner can be the same group but not necessarily.

Consumer

As the name suggests, consumes the service.

Just like the service provider, the consumer can be any of these types:

Group: a person or persona who uses the service. For example, end users may use an app to hail a taxi or find a rider (Uber). If the end user is a paying user, it is typically referred to as customer. When money is involved, there’s usually a Service Level Agreement (SLA) is in place. The user may also be internal. For example, an internal platform may be used by a group of developers. When the commitment is internal, usually a SLI and SLO is enough to communicate how reliability is measured and what is the level of service.

Component: same as the definition above. For example, a GraphQL API can be a consumer of upstream APIs. A mobile app can be the consumer of an identity service. A web page can be the consumer of tracking service.

System: same as the definition above. For example, Spotify’s web app is a consumer of their streaming, song catalog, and user tracking services among others. In this context, we don’t care to distinguish each individual component in the app (that information is probably irrelevant and abstract from the service provider perspective), so we see the whole web app as a system.

When the service consumer is a group of people, it may also act as a stakeholder but not necessarily. We’ll discuss the service stakeholder shortly.

Task

Task describes why the consumer uses a service. It may be an arcane word but it makes sense in the context of service levels. Failures threaten the task the consumer is trying to do.

Here are some other terms for “Task” that you might be familiar with:

Use Case describes how a consumer interacts with a system to achieve a specific goal. This term is also used in UML.

User Need describes why a user needs to use a service.

Jobs To Be Done (JTBD) was popularized by Tony Ulwick as a framework that suggests consumers buy products or services to get a specific job done rather than generic features or benefits. The actual “job” here is the task.

Providers have services.

Consumers have tasks.

A consumer may have multiple goals or tasks each of which can depend on a number of services that can be individually measured. This usage essentially establishes a dependency from consumer to the service provider.

The reason task is important in the context of service level is because of the biggest pitfalls of implementing service levels: to measure the wrong thing! Service level should always be measured from the perspective of the consumers. Task describes that aspect.

Failure

Failure describes how a task may not be successful. It is at the base of how [un]reliability is perceived from the perspective of the service consumer.

Failure is the opposite of the “level” in service level. Let’s see why.

Service Leve Indicator (SLI) is a positive concept as seen in the formula:

Note that there’s a small but important difference between valid and total.

Failure is a negative concept as seen in the formula for Service Failure Indicator (SFI):

SLO aims to optimize SLI while error budget aims to optimize SFI.

The reason failures are more important than success is because failures are important for alerting. Alerting is important for holding the service owner responsible for the service level objective (SLO).

One of the common pitfalls of implementing service levels is to measure what doesn’t matter from the service consumer’s perspective.

An effective way to make sure that you’re measuring the right thing is to ask whether it is worth to set alerting and on-call for it. If it’s just a mild inconvenience from the consumer’s perspective, maybe it is not worth waking up the on-call person. Instead you should find other metrics to measure more significant failures. We will discuss metrics shortly.

Failures have the following attributes:

Symptom: how does the consumer know that something is broken? There is a difference between symptoms and root causes. Symptom is how the failure is perceived by the consumer (e.g. HTTP 500 error) whereas the root cause is one or more issues that lead to that issue (e.g. the certificate is expired, API gateway cannot find upstream, Kubernetes cluster is down, etc.). In the context of service levels, we’re primarily interested to measure the symptoms. The idea is that if a potential root cause happens (e.g. CPU usage is through the roof), but no task is suffering, you should not wake up the on-call person in the middle of the night to investigate. That’ll just lead to alert fatigue and attrition.

Consequences: what is the consequence of the symptom? For example, if the page they’re trying to reach is the login page and they get a 500 error, they will be practically blocked out of most services and cannot do anything.

Business Impact: how would the consequences hurt the business? Companies are primarily interested to make money, and if a failure hinders that hunger, it impacts the business. In the above example, a user who cannot log in to the service may file for a compensation (if there’s a SLA in place), or take their money and go to the rivals. The consequence and business impact are related and maybe are the same thing when we’re assessing the risks towards an external consumer (also called customer), but for internal consumers, business impact is about translating the consequence to how the consumer’s failure becomes something the business cares about. For example, if a platform team (service provider) fails to provision a new repository (service) for the developers (service consumer) in a timely manner (symptom) because the underlying infrastructure faced an edge case (root cause), the developers get blocked (consequences) and the business is paying for their idle time (business impact).

Impact Level: while business impact describes how the business takes a hit from failures, the impact level puts that into perspective. There is a difference between users on an old version of Android being blocked from logging in than all users on all platforms not being able to check out their shopping card. The impact level of a failure usually fits nicely to incident severity categorization that is used for incident triage.

Likelihood: this is hard to predict but roughly speaking

risk = threat x likelihood: the more severe a threat and the more likely it is, the higher the risk. Therefore it’s good to have an idea about how likely a failure is, in order to prioritize preventing it.

Metric

Metrics quantify a behavior. They are at the core of Service Level Indicators which in turn are visualized as Service Level Status and trigger alerts to guarantee the Service Level Objective.

In the context of service levels, we’re primarily interested in metrics that quantify failure/success of the service provider from the perspective of the service consumer.

Example metrics: query latency, API error rate, queue length, timed-out requests, game rendering frame rate, GPU utilization, LLM token/second, etc.

You can think of a metric as an array of data points each with:

Value: what was the measurement

Timestamp: when that behavior occurred)

Metadata: For example, tags, labels, and annotations indicating the source, and providing more context about that measurement.

Data point type can be either:

Boolean: e.g., success of a probe checking if an endpoint is up, or whether a database record is up to date, etc.

Numeric: e.g., error rate, or request latency, etc.

Each data point may present:

A timeslot: e.g., if we probe an endpoint every minute, the status of the probe is extrapolated to assume the status of that endpoint over that entire minute

An event: e.g., a failed request, a cache hit, etc.

Timeslot data points are useful for time-based SLI whereas event data points are usually used for an event-based SLI.

An aggregation function (e.g., avg, min, max, percentile, sum, rate, etc.) can be used to convert an event metric to a time-based SLI. For example, you may use the P99 percentile value of every 5 minutes to represent that timeslot.

Just a reminder that a service can be automated (provided by a component or system) or manual (provided by a group of people).

Measuring the services provided by a group of people can be particularly challenging because not every manual operation leaves a trace that is quantifiable. That’s why you see things like this:

On the other hand, the biggest pitfall when measuring service levels of automated services is to measure the wrong thing or at the wrong place (we’ve covered the nuances of measurement location here).

Stakeholder

While the consumer’s perspective is the key to define the right service level indicator (SLI), the stakeholder has a say to what the service level objective (SLO) should be or how much error budget is acceptable.

Stakeholders are a group of people representing the interest of the business (which is ideally the consumer’s interest but not always).

Stakeholders can help assess the business impact and impact level of failures.

The paying end-users (also known as customers) are typically seen as a stakeholder because they have the money leverage. While that is true, there are typically internal stakeholders (e.g., PM or UX) who have every intention to keep the service level as high as possible. Ideally, they want 100% for everything. It’s important to manage their expectations with tools like the Rule of 10x/9 to add the cost of reliability into perspective.

Stakeholder is a key part of the negotiations for SLO which in turn shapes the alerting rules.

Stakeholders negotiate on behalf of the service consumer for a higher SLO

Service owners negotiate for a higher error budget

For internal service levels, the consumer team representatives (PM/EM/Tech lead, developers) act as stakeholders. Since your service is their dependency, they want you to measure what matters to them (SLI) and hold the service owner accountable for a high level of service (SLO).

For example, many companies do platform engineering. The platform itself is typically not a product that is sold to the end users, but rather is there to improve efficiency and productivity. The teams that use the platform should have a say in what metrics they want to be improved (SLI) for example:

Time to provision a new service

Time to deploy a change to production

Time to grant access to key systems to a new joiner

The stakeholders in this case are all the people who have a say in what good looks like. The sheer number of stakeholders is one aspect that makes platforms hard to get right. We’ll cover platform engineering as a product in another post.

Cheat sheet

Putting all these terms together, we get this relation map:

Service is a capability or feature that solves a problem for the consumers.

Service Provider provides the service and can be automated or manual. While service is an abstract concept (a solution to a problem), the provider is often a piece of technology like a microservice, an API gateway, or a database.

Service Owner owns the service. Ownership refers to 3 elements:

Knowledge: know the tech, its capabilities, and the problems that it is supposed to solve

Mandate: has enough control over the tech to improve the service level

Responsibility: with power comes responsibility. If the technical decisions lead to failure, service owner is responsible to fix it.

Service Consumer uses the services for their tasks and use cases.

Task describes why the consumer uses the service.

Service Failure describes what happens when the consumers cannot do their tasks using the service:

Failure Symptom: How the service failure is perceived from the perspective of the consumer? How would they know something is wrong with the service?

Failure Consequence: How will the consumer suffer when they cannot do their tasks because of the service failure?

Failure Business Impact: service is part of a product that makes or saves money for the business. How will the business suffer when a particular failure happens?

Stakeholder is the equivalent of the service owner on the consumer side and negotiates the Service Level Objective (SLO), even if it’s part of the SLA.

Service Level describes how the level of the service is perceived from the consumer’s point of view

Service Level Indicator (SLI) describes how the service level is measured.

SLI takes a metric and turns it into an indicator of failure/success events or time slots.

Service Level Objective (SLO) sets expectation on the service level

Service Level Status (SLS) quantifies the value of SLI at a given time. Its value can be graphed in direct relation to SLO.

Service Level Agreement (SLA) ties that expectation to some sort of guarantee (often financial and only when the consumer has a leverage). SLA contains at least one SLO.

One last thing: Product

With the language we’ve built, it’s very easy to define the product as a collection of services.

In other words, product is just another abstraction layer in the service level modeling.

Those services may be tightly coupled and or complementary to each other. It doesn’t matter. A product is a group of solutions to fulfill consumer tasks.

This is particularly useful for teams with internal stakeholders or consumers. For example, internal platform teams or common components used by many apps.

This definition of product unlocks very power perspective:

It separates the concerns of the consumers from that of the service owners

It can guide the architecture of service providers for lose coupling and separation of concerns

It can by extension guide the organizational architecture to map to the logical grouping of service providers

A good usage example of this mental model is platform products. Quite often I hear the platform teams ask “what is our product?”

The answer can easily be deduced by defining their services in terms of what they solve for the rest of the organization and why do they exist.

Organizing the teams to streamline the consumer journey is a good way to implement full ownership:

My monetization strategy is to give away most content for free. However, these posts take anywhere from a few hours to a few days to draft, edit, research, illustrate, and publish. I pull these hours from my private time, vacation days and weekends.

Recently I went down in working hours and salary by 10% to be able to spend more time learning and sharing my experience with the public. You can support this cause by sparing a few bucks for a paid subscription. As a token of appreciation, you get access to the Pro-Tips sections as well as my online book Reliability Engineering Mindset. Right now, you can get 20% off via this link. You can also invite your friends to gain free access.

You can also refer your contacts and gain free subscriptions. Thanks in advance for helping these words reach further and impact the software engineering community.

Another one: "Impact Level: while business impact describes how the business takes a hit from failures, the impact level puts that into perspective. There a difference between users..."

Should be "There *is* a difference..."

There is an error in this sentence: "Service Stakeholder is the equivalent of the service provider on the consumer side and has a say in service level objective (SLA)." It should be SLO and not SLA.